Attacking OTP Using a Biased Key Generation

This writeup is also readable on my GitHub repository and team website.

This is my third and final writeup from this year’s ImaginaryCTF. This particular challenge concerns attacking an OTP (one-time pad), a strong encryption technique in cryptography that is fundamentally uncrackable given proper implementation and adherence to a few simple rules dictating its key. My team’s solution involved exploiting a bias in the key generation of a vulnerable OTP implementation to recover a flag.

crypto/otp

Challenge written by Eth007.

Encrypt your messages with our new OTP service. Your messages will never again be readable to anyone.

nc otp.chal.imaginaryctf.org 1337

Files: otp.py

Checksum (SHA-1):

9543af6baf0db5286ce756e5fe47f7686b999030 otp.py

Before beginning, it’s necessary to understand what OTP is. OTP is an encryption technique that requires a pre-shared key of equal or greater length than its message, which is used to encrypt or decrypt each unit of data in a stream. The one-time pad gets its name from cryptographers of old who would write these secret keys onto single-use pads of paper.

Modern OTP encrypts plaintext bits with bits from a pre-shared key using an XOR (exclusive-or) operation. An XOR operation, also represented by the symbol \(\oplus\), outputs a “1” if and only if one of the arguments is a “1,” but not both.

As an example, suppose that I wanted to send you a message. We would first have a pre-shared key that is randomly generated, and I cannot stress enough that it is extremely important that the key is randomly generated.

Suppose we both know the key to be: 11010101 00101010 11100101 01001010 11101000. This is pre-shared.

Now, I will send you the ciphertext through the air: 10011101 01001111 10001001 00100110 10000111. Even if an attacker were to intercept this, they cannot read it without the pre-shared key.

You receive the ciphertext and perform an XOR operation to recover the plaintext:

\[\begin{array}{ccc} & 10011101 01001111 10001001 00100110 10000111 & Ciphertext \\ \oplus & 11010101 00101010 11100101 01001010 11101000 & Key \\ \hline & 01001000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111 & Plaintext \end{array}\]01001000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111 is “Hello” in ASCII.

In order to ensure OTP’s unbreakability, the following four conditions must be met simultaneously:

- The key must be at least as long as the plaintext.

- The key must be random (uniformly distributed in the set of all possible keys and independent of the plaintext), entirely sampled from a non-algorithmic, chaotic source such as a hardware random number generator. It is not sufficient for OTP keys to pass statistical randomness tests as such tests cannot measure entropy, and the number of bits of entropy must be at least equal to the number of bits in the plaintext. For example, using cryptographic hashes or mathematical functions (such as logarithm or square root) to generate keys from fewer bits of entropy would break the uniform distribution requirement, and therefore would not provide perfect secrecy.

- The key must never be reused in whole or in part.

- The key must be kept completely secret by the communicating parties.

- Wikipedia

With a foundational understanding of OTP out of the way, we can now discuss the CTF challenge. Reading the given source code shows a homemade OTP implementation:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from Crypto.Util.number import long_to_bytes, bytes_to_long

import random

import math

def secureRand(bits, seed):

jumbler = []

jumbler.extend([2**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([3**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([4**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([5**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([6**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([7**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([8**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([9**n for n in range(300)])

out = ""

state = seed % len(jumbler)

for _ in range(bits):

if int(str(jumbler[state])[0]) < 5:

out += "1"

else:

out += "0"

state = int("".join([str(jumbler[random.randint(0, len(jumbler)-1)])[0] for n in range(len(str(len(jumbler)))-1)]))

return long_to_bytes(int(out, 2)).rjust(bits//8, b'\0')

def xor(var, key):

return bytes(a ^ b for a, b in zip(var, key))

def main():

print("Welcome to my one time pad as a service!")

flag = open("flag.txt", "rb").read()

seed = random.randint(0, 100000000)

while True:

inp = input("Enter plaintext: ").encode()

if inp == b"FLAG":

print("Encrypted flag:", xor(flag, secureRand(len(flag)*8, seed)).hex())

else:

print("Encrypted message:", xor(inp, secureRand(len(inp)*8, seed)).hex())

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

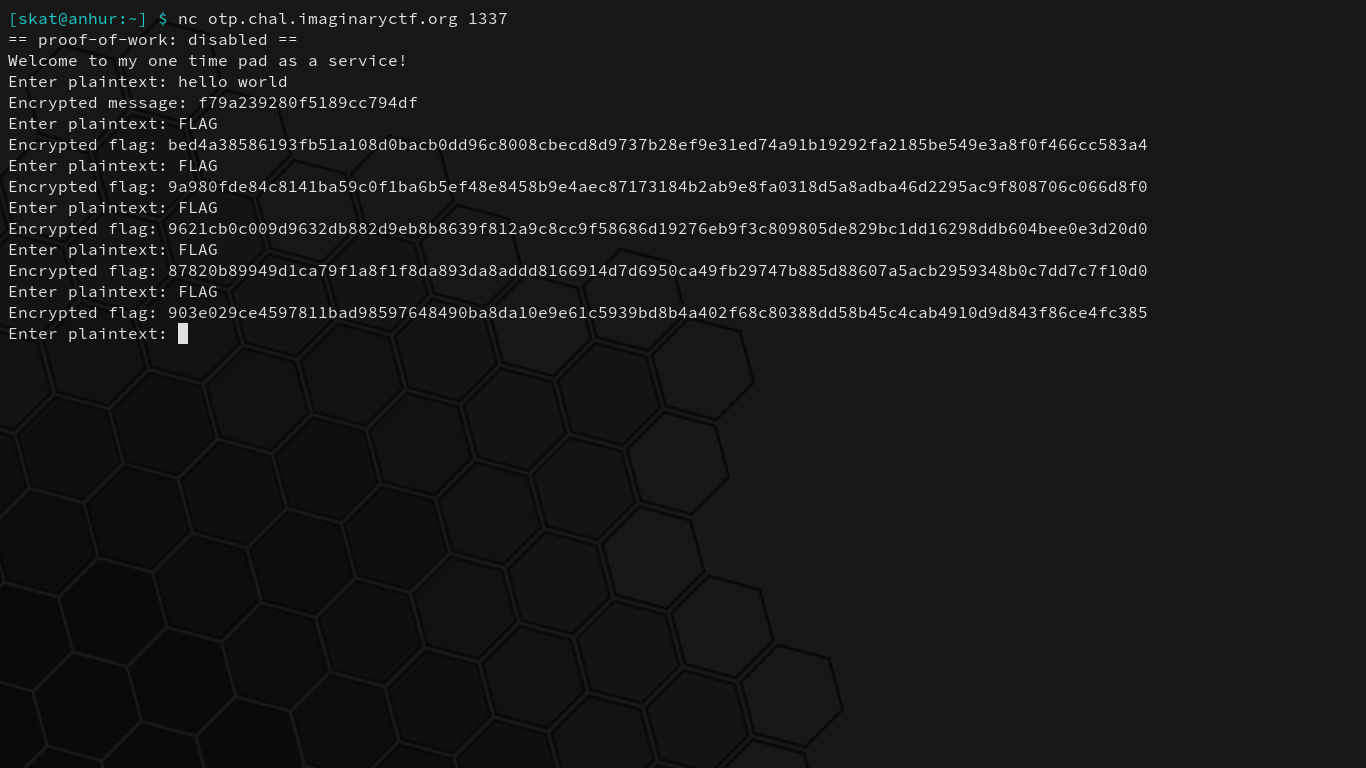

This program reads the flag and then encrypts it, and then allows you to either get the encrypted flag or enter a plaintext and see its encrypted counterpart. While the seed stays constant throughout a running instance of the program, the keys continue to change seemingly randomly:

At first glance, it may not be apparent what the vulnerability is. One’s eye may pop out at the jumbler. A keen eye will be attracted to this specific section of the key generation code:

if int(str(jumbler[state])[0]) < 5:

out += "1"

else:

out += "0"

If the first digit of a chosen number in the jumbler is less than 5, a “1” bit is appended to the key. Otherwise, a “0” bit is appended. This seems okay until you remember that numbers cannot start with 0, so while 4 possible digits can create a “1,” 5 possible digits can create a “0.” This will, however, not create a 44.4%/55.5% split in probability for reasons that will be explained in a moment. There may be a bias in key generation here, which we should explore more deeply.

In order to better determine whether or not a bias exists in key generation, I modified the source code to analyze the probability of any given bit being a “1” in 10000 keys:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from Crypto.Util.number import long_to_bytes, bytes_to_long

import random

import math

def secureRand(bits, seed):

jumbler = []

jumbler.extend([2**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([3**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([4**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([5**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([6**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([7**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([8**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([9**n for n in range(300)])

out = ""

state = seed % len(jumbler)

for _ in range(bits):

if int(str(jumbler[state])[0]) < 5:

out += "1"

else:

out += "0"

state = int("".join([str(jumbler[random.randint(0, len(jumbler)-1)])[0] for n in range(len(str(len(jumbler)))-1)]))

return out

def main():

# A random string in flag.txt will suffice.

flag = open("flag.txt", "rb").read()

seed = random.randint(0, 100000000)

print("Generating samples...")

samples = [secureRand(len(flag)*8, seed) for _ in range(10000)]

probOne = [0 for _ in range(len(samples[0]))] # Probability of a bit in the key being a 1.

print("Analyzing...")

for sample in samples:

for i, bit in enumerate(sample):

if bit == "1": probOne[i] += 1

for i, stat in enumerate(probOne):

print("Bit %d probability of being '1' is %.2f%%" % (i, stat/len(samples) * 100))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Interesting. There’s a 70% probability of any given bit in the key being a “1,” contrary to our earlier estimate of 44.4%. This has to do with the fact that we’re not simply generating a number from 1-9 (inclusive) and checking whether or not it’s less than 5, but rather that we’re selecting the first digit in a chosen number from a set of numbers: the jumbler.

jumbler = []

jumbler.extend([2**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([3**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([4**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([5**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([6**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([7**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([8**n for n in range(300)])

jumbler.extend([9**n for n in range(300)])

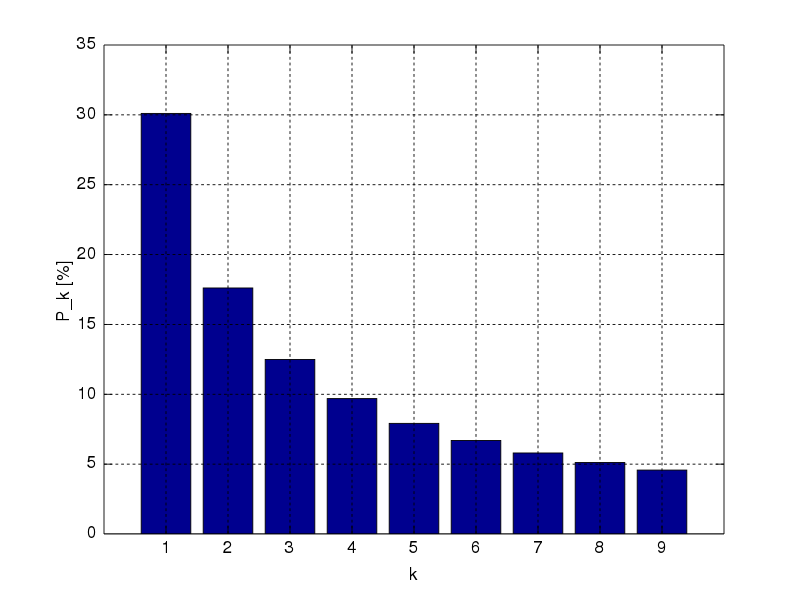

Benford’s Law explains this phenomenon. The leading (first) digit in any given number in a real number set is likely to be small. The distribution of first digits according to Benford’s Law looks like so:

\(P(d)\) from \(d \in \{1,..,9\}\) are 30.1%, 17.6%, 12.5%, 9.7%, 7.9%, 6.7%, 5.8%, 5.1%, and 4.6%, respectively, as per the probability equation:

\[\begin{align} P(d) &= log_{10}(d+1) - log_{10}(d) \\ &= log_{10}\left(\frac{d+1}{d}\right) \\ &= log_{10}\left(1 + \frac{1}{d}\right) \end{align}\]Graph, numbers, and equations courtesy of Wikipedia.

When the digits that can create a “1” bit in the key are 1, 2, 3, and 4, the sum probability of a “1” bit being created in the key are 30.1% + 17.6% + 12.5% + 9.7% = 69.9%. This explains our findings from our analysis of 10000 samples earlier.

We’ve discovered a violation of rule 2 of unbreakable OTP, meaning that this implementation of OTP can be cracked:

The key must be random (uniformly distributed in the set of all possible keys and independent of the plaintext), entirely sampled from a non-algorithmic, chaotic source such as a hardware random number generator.

As the key is not truly randomly generated, the ciphertexts, therefore, are not either. We can simply gather a large number of flag ciphertext samples from the server, compute the probabilities of each individual bit to form a single binary string, and then XOR it with 1s to retrieve the flag. This is easily automated with pwntools in Python:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

from pwn import *

def main():

target = remote("otp.chal.imaginaryctf.org", 1337)

log.info("Gathering samples...")

samples = []

for i in range(100):

target.recvuntil(b"plaintext: ")

target.sendline(b"FLAG")

data = target.recvline().decode("utf-8").split()[-1]

log.info("Received sample: %s" % data)

samples.append(bin(int(data, 16))[2:].zfill(len(data)*4))

probOne = [0 for _ in range(len(samples[0]))]

log.info("Analyzing...")

for sample in samples:

for i, bit in enumerate(sample):

if bit == "1": probOne[i] += 1

binary = ""

for stat in probOne:

if stat/len(samples) > 0.5:

binary += "1"

else:

binary += "0"

dataBytes = [int(binary[i:i+8], 2) for i in range(0, len(binary), 8)]

flag = "".join([chr(b ^ 0xFF) for b in dataBytes])

log.info("Flag: %s" % flag)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

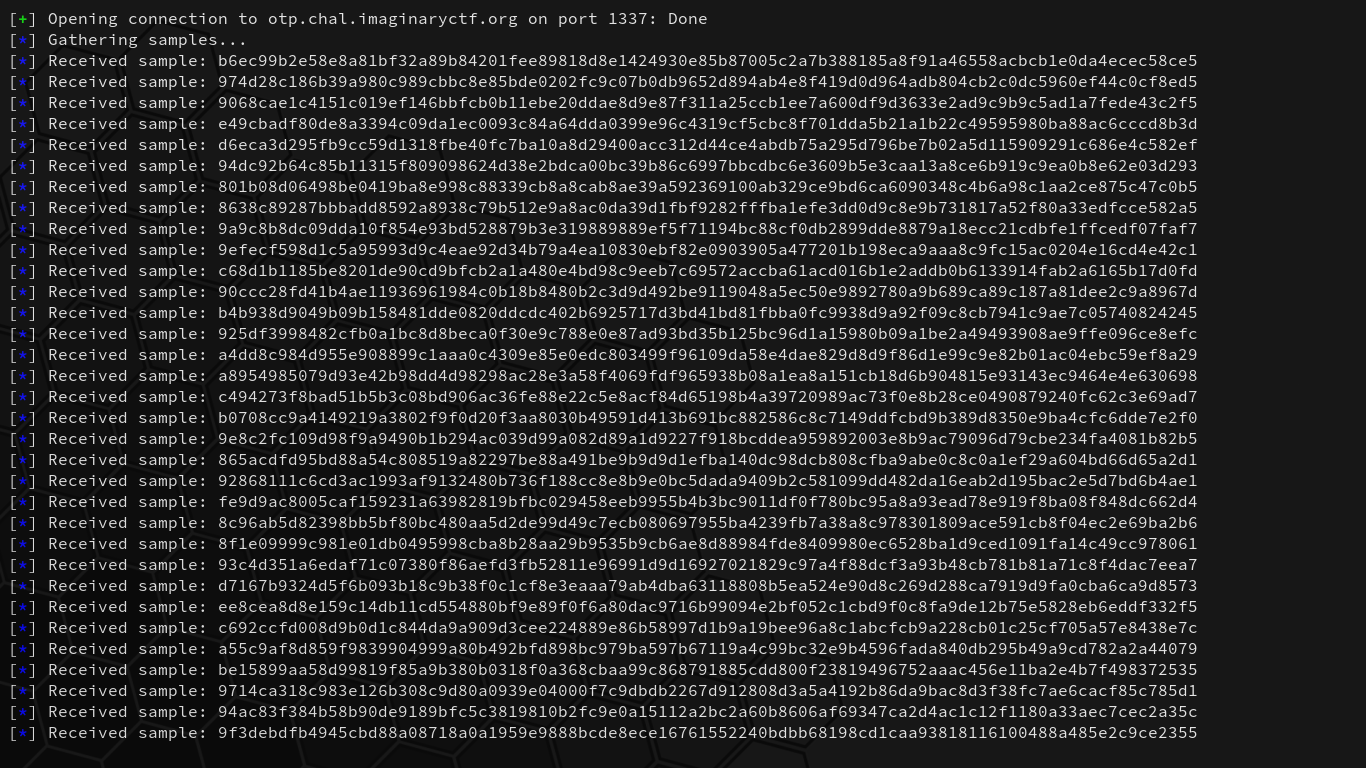

Upon running the script, we begin capturing samples:

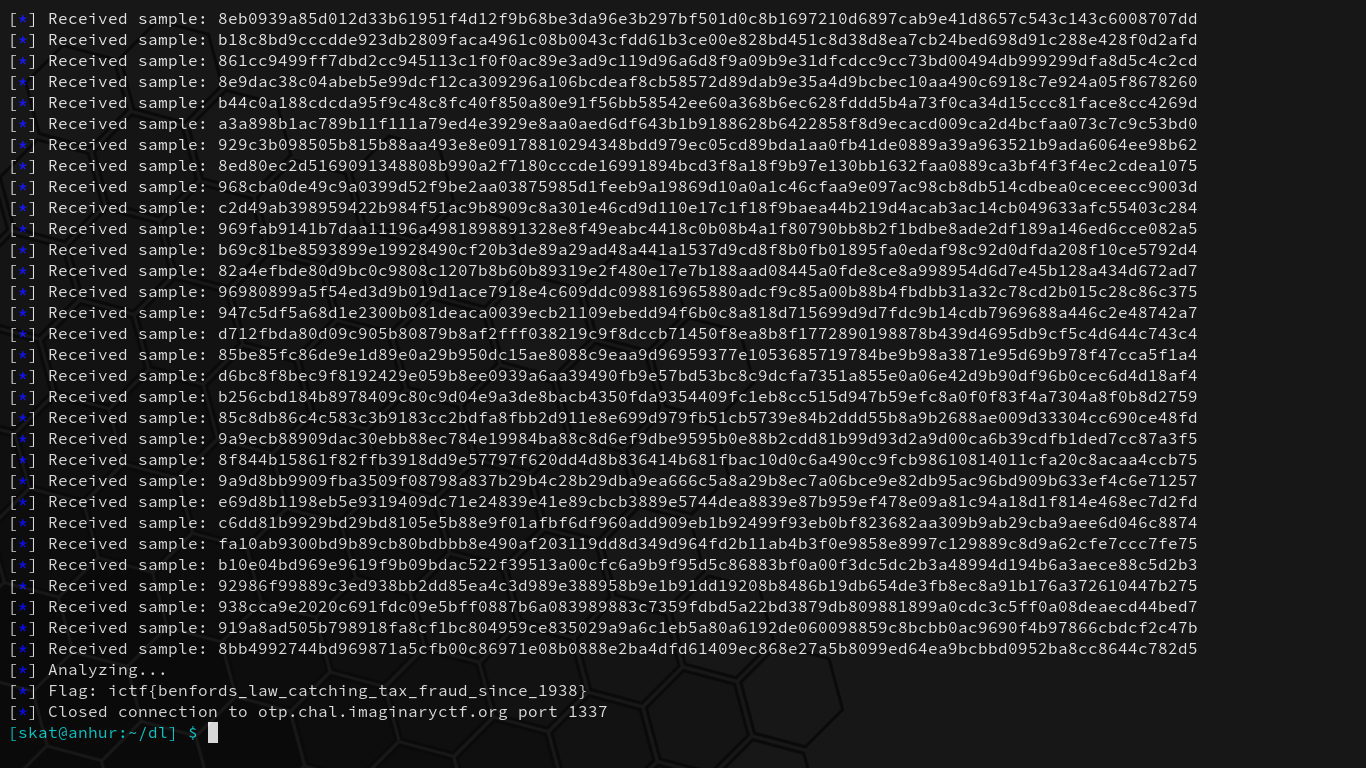

After 100 collected samples, our script computes the most common bits for each position and then creates a single binary string with the higher discovered probability bits. The binary string is then converted to their respective bytes as integers and then XORed and converted to ASCII by 1s:

What a lovely and deeply satisfying challenge. By forming an important foundational understanding of OTP and analyzing the given code, we discovered a bias in key generation and found that it violates the randomness rule of uncrackable OTP implementation, eventually leading to recovering the flag. We’ve successfully cracked the encryption.

Happy hacking!